A–Z

— OF EYEWEAR —

BY STEENIE

NORVILLE

Whenever I’m asked to provide eyewear for theatrical productions, my first call is to Norville. Matilda is a case in point. The character of the cook needs huge and crazy magnifying glass-type lenses. The additional headache is that the poor actor needs to see through them, too. Norville custom-made for me a lens within a lens with a different prescription in the middle so our girl could see and act at the same time. Very few companies could take on such a job. In many ways, Norville are the last bastion of a certain type of British manufacturer. Founded just after the second world war and based in Gloucester, Norville’s core business is lenses, though they can, have and will do anything. This moves completely in the other direction to most large manufacturers, like Hoya and Essilor, who the bigger they become, the less they can do. Over-proceduralised, they can mass-produce vast quantities of the same unit on any given day but a one-off, eccentric job, like fashioning a lens-within-a-lens for the cook in Mathilda won’t be cost effective. In some ways, Norville harks back to when spectacle manufacturers had such pride in their calling that they would make anything for you as a matter of almost honour.

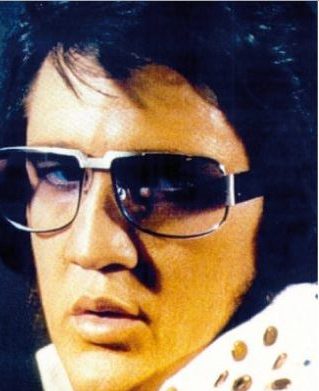

NEOSTYLE

If anyone knows anything at all about German designer Neostyle, it’s that they made the Nautic frame, with its thick arms and funky, chunky bling look beloved of Elvis Presley who used to love to personalise and create his own singular pieces. The association with Elvis certainly put the Stuttgart designer on the map. Neostyle’s founder, Walter Nufer, is one of the first people, alongside Schmeids of Silhouette fame and Tony Gross in Britain who really wanted to see eyewear as a fashion accessory, an object of desire in and of itself, and not a medical appliance. It’s a shame that Neostyle is only known for the Nautic as they went on to create a lot of fun frames especially in the 80s.

NIKON

They make cameras, Japanese cameras, so their lenses must be among the best, their name a guarantee of quality and craftsmanship. We all do this, don‘t we? Trust the brand. The name has always been there, on TV, in the ads in glossy magazines, coded into conversation as a byword for style or a certain standard. We all go with what we’ve heard of, and we’ve heard of Nikon. Don’t get me wrong. Nikon do make decent lenses. In my humble opinion, Hoya make better lenses, but Nikon make good lenses. What you might not know is that Nikon is owned by someone else, that the lens industry is as prone to monopolies, is the domain of a handful of global players much like fast food or high-street fashion retail and anything sellable that you can think of.

Nikon is owned by Essilor, who are part of Luxottica-Essilor, the biggest eyewear company in the world. On their way up, the wannabe global corporation gobbles up companies like Nikon to purchase a charade of quality, recognition and reassurance, the mark of a high-quality brand you can trust. The problem is: You can’t always trust it. Like: Pentex used to be a quality brand. Seiko used to be a quality brand. When Hoya bought Pentex and Seiko it thought it couldn’t have two quality brands in competition with one another, so it repurposed Pentex as a budget range. However, you still think Pentex lenses are Pentex lenses. You buy a pair of budget glasses but think you’re getting quality because the lenses are, after all, still Pentex. Of course, if you use an independent and experienced optician, we’ll always advise you to buy the best lenses for you even if you’ve not heard of the manufacturer. We’ll guide you towards things that you didn’t know about.

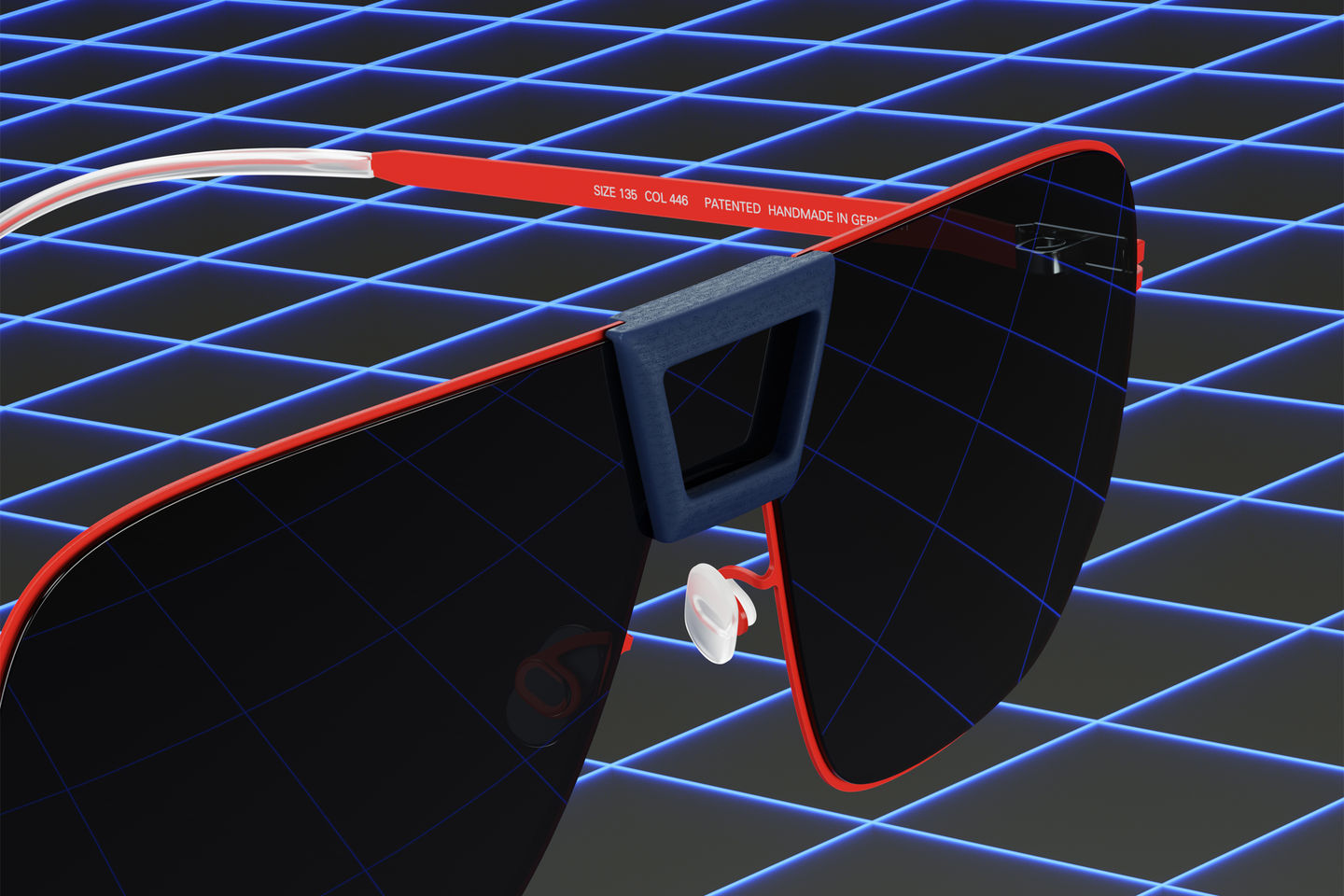

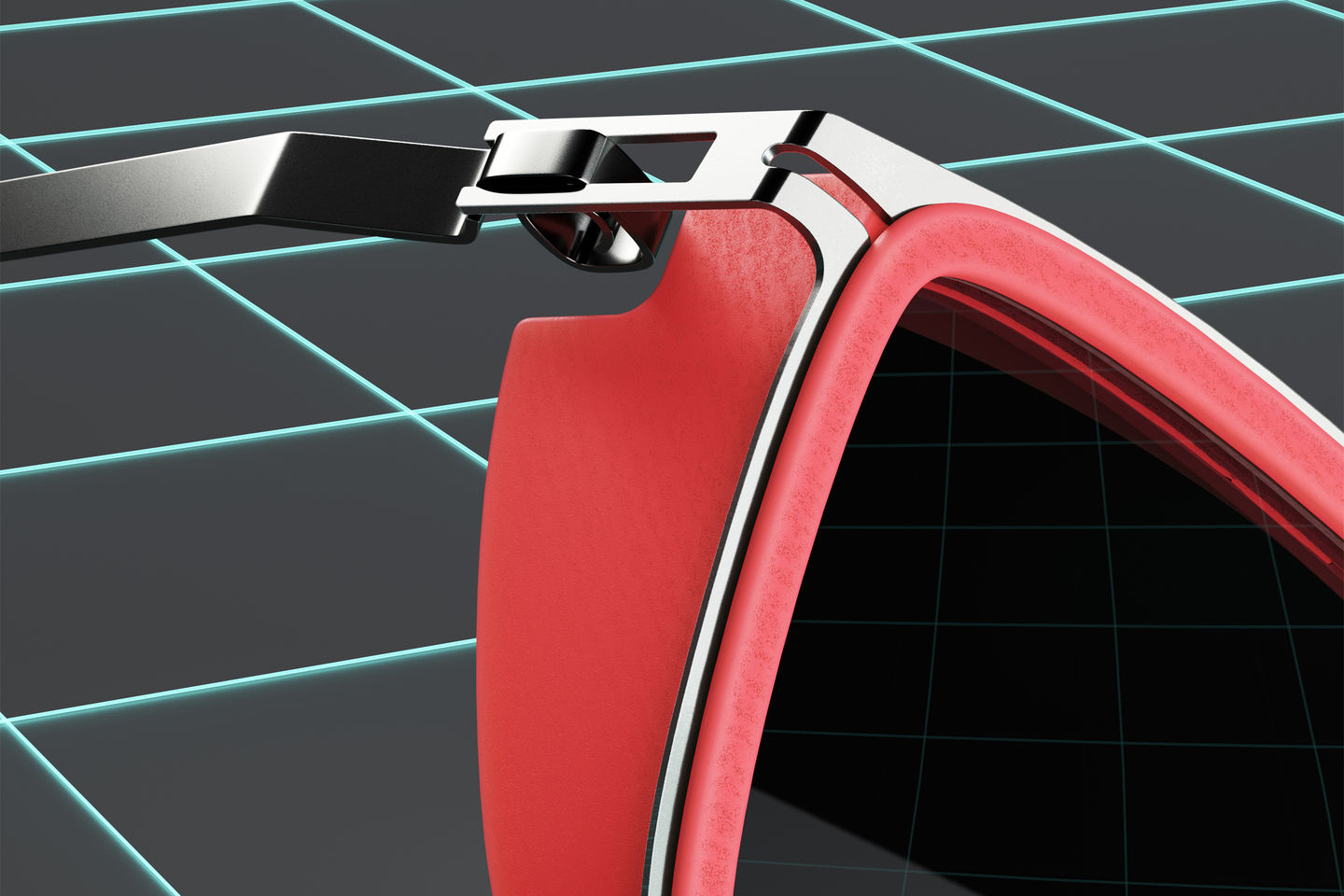

NYLON

Sounds dull but it’s actually an intriguing and versatile material. It’s used in plastic injection moulding and in the manufacture of budget-end eyewear, your five quid tourist sunglasses you might buy at a beach shack. It’s easy to mould and very cost effective because after the initial outlay, you’re only paying for the fluid. So, it’s the cheap stuff, and it’s not adjustable or bendable, but on the other hand it’s damn-near unbreakable, so robust it’s used by lots of high-end sports brands. We’re going to see a lot more of it soon as it’s used in 3D printer sintering. The Mykita Mylon is one of the first sintered ranges of sunglasses to glide into the world. They will not be the last.

Mykita Mylon campaign images 2019

NYLOR

In 1955 Essilor invented a new, revolutionary frame that was to become a signature of that particular age of eyewear fashion: the Nylor. No one had seen anything like it before. It has a metal or acetate upper frame but a rimless bottom. A nylon wire that fitted into a groove in the lens held it all in place. They were stylish and practical, given that when you were reading the lower parts of a frame did not get in the way.

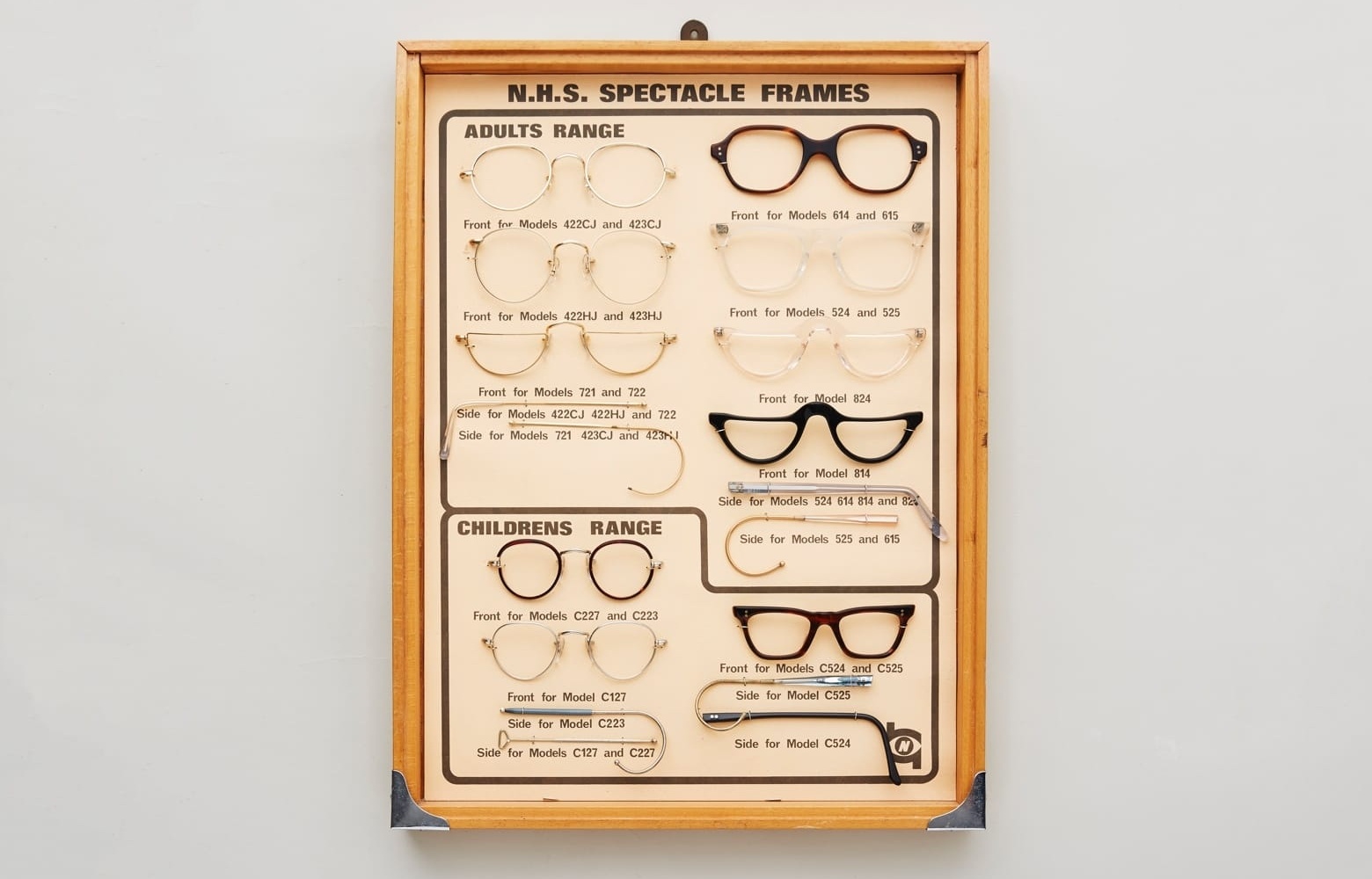

NHS

NHS spectacles were a prominent part of the great social experiment that followed the second world war and the foundation of the Welfare State. For the first time ever, everyone was entitled to pair of government-sponsored glasses.

Like a lot of people, I used to cringe at the prospect of NHS glasses. Like many more now, I look back on them with new respect and nostalgia for things passed. The immediate post-war period was boom time for opticians as millions of people who had never even had an eye test before were encouraged to do so. The first ranges were launched in 1949.

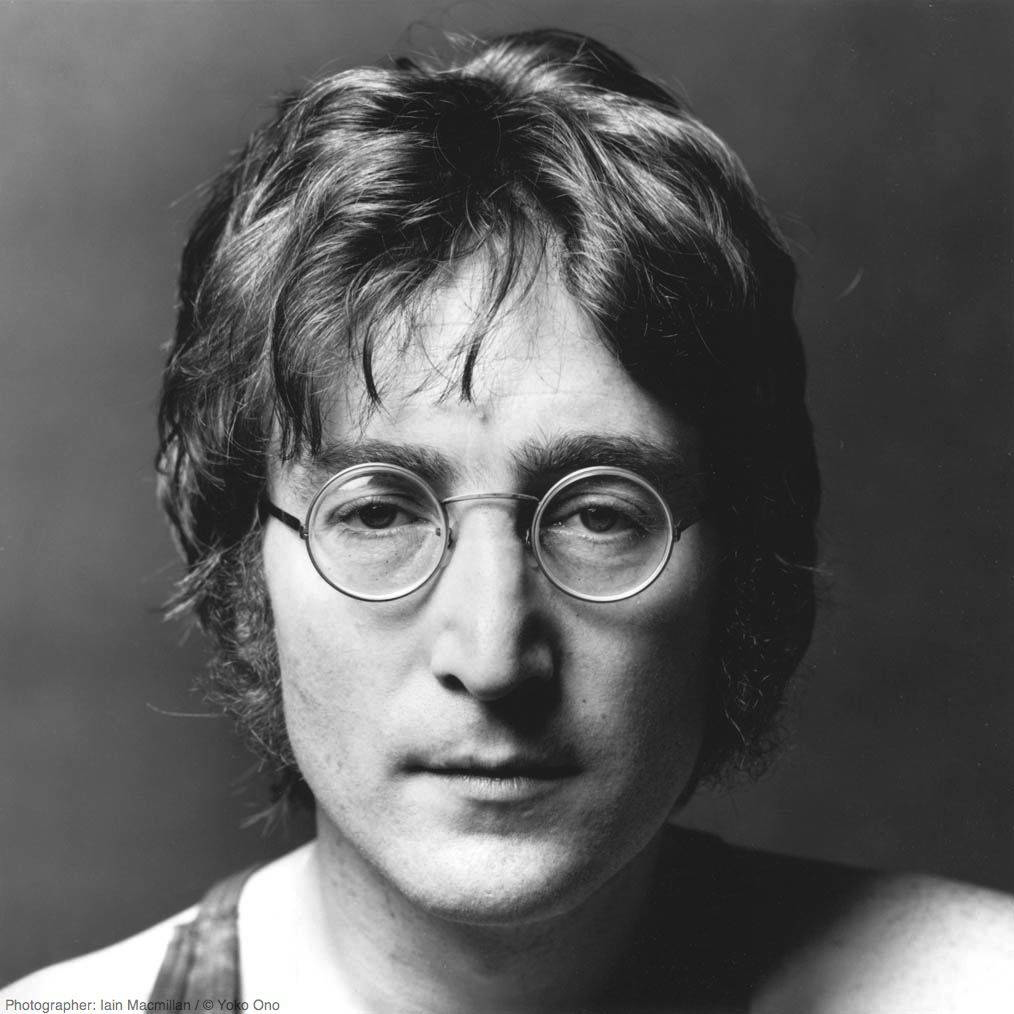

The two main frames, the 422 metal frame, (the Lennon) and the 524 acetate frame (the Morrissey) turned out to be pieces of great quality and ultimately iconic design classics. Getting free glasses, though, made people the object of derision and NHS specs were associated with badly-dressed OU lecturers, low-grade officials and bumptious bores, like Dad’s Army’s Captain Mainwaring, the sort of people you wouldn’t want to be like.

In 1985, the Thatcher government stopped the free flow of NHS specs. If you were not on benefits, you had to buy your own. A great swathe of British manufacturing companies involved in the production of NHS glasses disappeared and with them a skilled workforce. A world of talent vanished. It wasn’t long after that what had seemed like the epitome of uncool has become cool again.

In 1989, Georgio Armani was the first fashion designer to launch a range of eyewear and boy did he summon up the ghost of the 422. The whole collection owes a great debt to the NHS and glasses a few years before the cognoscenti wouldn’t be seen dead in.

We reach an interesting pivot here in the history of eyewear design. Beforehand, from the 30s onward, each decade had its own look, its own innovations, its cats eye or nylor or Futura but now we’re styling retrospectively, looking back rather than looking forward, as if our future is in the past, that the future will only be worse than the present and its only in the past that we can be happy, only in the past that we can be cool or charismatic. 70s designs are very much back in vogue now. They’re all coming back. Where do we go from here? Where will we go once we catch up with the 80s and its look-back buzz?

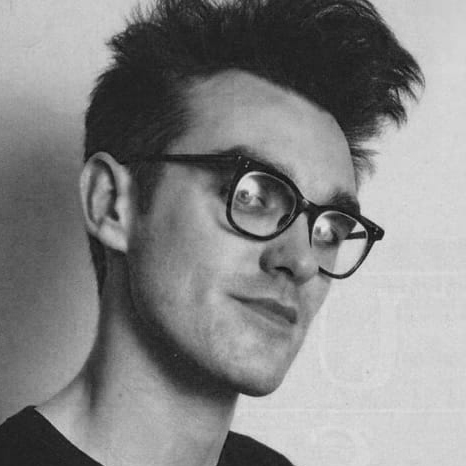

Left: Morrisey in 524 Acetate NHS frame.

Right: John Lennon in 422 Metal NHS frame